The Archaeology of African-American Life in St. Georges Hundred, Delaware, 1770-1940

Created by John Bedell and Jason Shellenhamer, the Louis Berger Group, Inc.

HISTORICAL NARRATIVE, 1770-1940

The story of African Americans in St. Georges Hundred mirrors their story across America: by great effort they raised themselves from enslavement to independence, slowly winning their legal rights and decent homes and lives. Despite intense prejudice, they found ways to get by, and form enduring communities.

Almost all the Africans who came to America before 1865 were enslaved, and in those years their story is dominated by issues of slavery and freedom. While enslaved, they struggled to establish stable lives despite harsh conditions. They also longed for freedom, and some took terrible risks to achieve it through rebellion or, more commonly, running away. Once they were legally free, their troubles were far from over, since African Americans were subject to many legal and practical limitations on their actions and hampered by limited economic opportunity. Slowly, they built up their world: started families, founded churches, established communities.

In Delaware some African Americans achieved freedom before the Revolution, and many more gained their freedom over the years from 1776 to 1800. Delaware remained legally a slave state until 1864. However, Quakers and other opponents of slavery had much influence in the state, and they persuaded many owners to grant freedom to their enslaved workers. By 1800, when the first surviving census was taken, about half the African Americans in the state were free. Some of these people had remarkable careers. Several owned land, and a few grew wealthy. Most, however, struggled with poverty and had great difficulty establishing their own households. They faced legal discrimination and the constant threat that they, or their children, might be kidnapped and sold into slavery in the South. Despite this adversity, many African Americans in Delaware, free and enslaved, helped the Underground Railroad transport people who had escaped bondage toward freedom in the North. After about 1830, African Americans began to make real progress in establishing independent households and communities.

In 1800, about a thousand African Americans lived in St. Georges Hundred. Over the course of the next 80 years that number slowly rose, reaching 2000 in 1870, making up 30 to 40 percent of the total population of the Hundred. In the late 1700s, most lived in households headed by whites, working as farm laborers or domestic servants. Over time the number of independent African-American households steadily grew, and by 1880 more than three quarters lived in households headed by African Americans. Economic progress was also slow. As late as 1900 most African American men in the hundred still worked as laborers, and most employed women worked as domestic servants. St. Georges Hundred was farm country, so most of these laborers worked in fields and orchards. Not until the 1920s, with the economy diversifying, did opportunities for African Americans to work in other industries open up.

Besides the end of slavery, the most important development for African Americans in St. Georges Hundred over this period was the founding of churches and the growth of communities around them. In 1770,there were few African American churches, and most African Americans attended churches run by and mostly for whites. The founding of separate black churches gave African Americans institutions that were truly theirs. The local churches provided both a spiritual home and a physical meeting place for African Americans, and as the national churches grew to have many thousands of members, they provided a path to leadership roles for the able and ambitious. Churches also became the centers of communities. Each of the four African American communities in St. Georges Hundred was centered on a church. It was at the church that people met to reaffirm their community ties. St. Georges Hundred was mostly rural and homes were spread out, but African American houses clustered around the churches where people found fellowship. The first African American congregations in St. Georges Hundred were founded around 1830, and the first church building was constructed in Odessa in 1845.

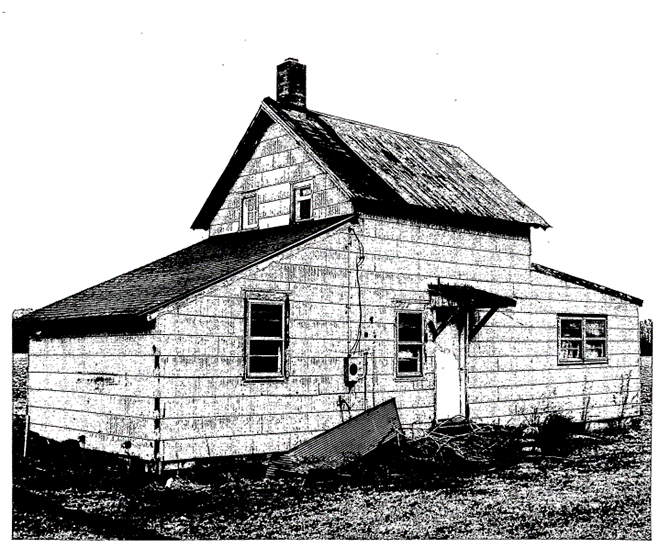

Beginning in the 1860s, schools were also set up in each African American community. These provided both education for children and another focus for community life. By 1880 most African American children in St. Georges Hundred got at least some schooling, and this contributed to the economic advancement that took place after 1900. In the twentieth century, St. Georges Hundred began to change. Modern farming replaced much farm labor with machinery, so farm laborers moved to cities to find work. The population of rural areas like St. Georges Hundred fell. Most of the old frame tenant houses that used to line roads in the Hundred were torn down and the house sites plowed under for more corn, soybeans and wheat. The African American communities of Congo Town and Armstrong Corner disappeared. Those in Middletown and Odessa can still be found, or at least some of the buildings can. But for rural areas we have only the old records, and the findings of archaeology.